|

"Cemeteries today play many roles in the lives

of the living. In a relentlessly urban environment, they are

used as visitor attractions peaceful and green open spaces, outdoor

art galleries, sites of pilgrimage, places to play, to sleep,

to have sex, to think, to walk the dog, to hang out with friends,

or maybe to have a beer. But this can sometimes be vulnerable

to development plans and the demands for new housing, roads and

services for the living. With the intense competition for space

in London today, little space is available for the living, let

alone the dead."

London is running out of burial space.

Inner London boroughs have on average seven years' burial space

left. Two of them, Hackney and Tower Hamlets, have no space left

at all. With intense competition for space, do we still have

room for the dead, and if so, where?

Photographs of crematorium interiors and oral recordings of people

involved in the disposal of the dead offered insight into professions

rarely discussed in public.

Objects on display explored the many

facets of our attitudes to death. They ranged from an Early Bronze

Age cremation urn and recently excavated Roman grave goods to

an environmentally friendly contemporary cardboard coffin.

An exhibition of wicker coffins in 1875

Francis Seymour Haden's 'Earth to 'Earth' system was based on

allowing the body to decay naturally. He believed that burial

in wooden coffins resulted in 'festering tenants inperpetuity

of the soil' and that cremation would needlessly pollute the

air. He promoted the use of easily degradable coffins, notably

wicker coffins, arguing that they would enable burial in the

same land every five or six years.

|

This display explored issues we would

rather not face and asked the question - what will happen to

our bodies when we die?

How should Londoners dispose of their

dead? People came and aired their views at a debate on 6 September,

when the motion was: 'Must London face up to reusing graves?'

Memento Mori - Contemporary

photography by Agustin Amate Bonachera Memento Mori - Contemporary

photography by Agustin Amate Bonachera

31 August 2000 to 8 October 2000

In a series of photographs of Victorian and Edwardian sculpture

in the cemeteries of London, Agustin Amate Bonachera explores

the transient nature of human existence, capturing a society's

belief in the divine and immortal.

|

|

Coffin plate and mourning jewelery

|

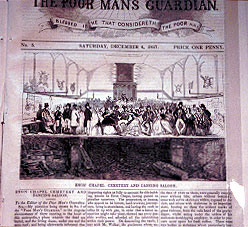

Enon Chapel Cemetery and Dancing Saloon, in The Poor Man's

Guardian,1847

Between 1822 and 1842 the Minister of Enon Street Baptist

Chapel in Clements Lane Facilitated the disposal of an estimated

10?12,000 people in its cellar removing bodies when more space

was needed this edition of The Poor Man's Guardian featured responses

to an earlier report which described how while dances were held

in the chapel above in the cellar below on all sides lay human

remains broken coffins and other emblems of decayed mortality

|

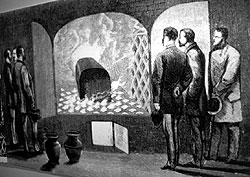

Sir Henry Thompson demonstrating :

a cremation oven in 1874

Published in illustreret tidende, 1874

In 1874 Sir Henry Thompson, surgeon to Queen Victoria, founded

the Cremation Society and began to promote cremation. He argued

that it was a more sanitary method of disposal and less space

consuming than burial, as well as being more economical. After

initial Home Office hesitancy, the first official modern cremation

of a person took place in 1885 and a Cremation Act was passed

|

Headstone 12th?13th century

This headstone, of Purbeck marble, was found during excavations

on the site of ] Poultry. The headstone came from the graveyard

of St Benet Sherehog, a small parish in the City of London. On

one side a cross is carved, on the other side an inscription

reads:

'H[ic] iacet in tumbo coniu[n]x alicia petri'

'Here lies in this tomb, Alice the wife of Peter' |

A Bill of Mortality, published weekly summary of deaths during

the Great Plague |

Disposal of plague

victims

One in three Londoners died during the Great Plague of London

in 1665.

Myths and misconceptions have developed concerning the location

and methods of disposal of victims.

Evidence suggests that, contrary to popular belief the process

of burying the dead during the plague was well managed, with

bodies being carefully laid out and buried in shrouds or coffins.

Where possible existing graveyards coped with the rising numbers

of dead. As yet, no specific plague pits have been excavated

for the 1665 plague. |

In loving memory of West Norwood Cemetery,

by Geoffrey Manning, 1989

Published by the Norwood Society, this booklet was a guide to

the most significant memorials in West Norwood Cemetery. Since

Lambeth Council purchased the cemetery in 1965, a 'lawn clearance'

programme has resulted in the removal of over 10,000 memorials.

The council is now working to repair and restore some of them.

It also resold over 900 graves following 1970s legislation permitting

municipal cemeteries to sell unused burial space within existing

graves over 75 years old.

In 1994 a Southwark church court had judged the resale of graves

at west Norwood, as it was originally a private not a municipal

cemetery, to be illegal |